Rocks have always played a significant role in shaping landscapes, ecosystems, and human activities. Among the many geological features found in nature, projecting rocks stand out due to their striking presence and importance. Projecting rocks are those that extend outward from the earth’s surface, cliffs, or slopes, often appearing as ledges, outcrops, or overhanging formations. They may seem like simple natural structures, but their role in geology, ecology, safety, and even culture is far-reaching.

What Are Projecting Rocks?

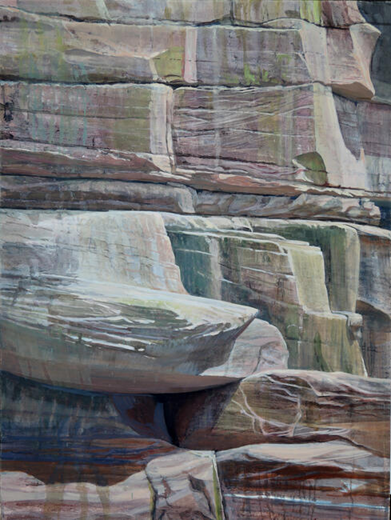

Projecting rocks are solid masses of rock that jut out from a hillside, mountain, or cliff face. Unlike loose stones or boulders, they are firmly attached to the earth’s crust, making them part of the larger bedrock system. These formations can vary in size from small ledges to massive overhangs that stretch across valleys. Their shape and appearance are influenced by natural forces such as erosion, weathering, tectonic movement, and water flow.

For example, in mountainous regions, projecting rocks often develop when softer layers of stone erode faster than harder layers, leaving behind resistant rock ledges. Along coastlines, waves carve into cliffs, producing dramatic rock projections that overlook the sea.

How Do Projecting Rocks Form?

The formation of projecting rocks is the result of complex geological processes that unfold over millions of years. Some of the primary factors include:

-

Erosion and Weathering – Wind, rain, ice, and temperature fluctuations gradually wear down rock surfaces. When softer materials erode faster, harder layers protrude outward, forming ledges.

-

Tectonic Activity – The movement of the earth’s plates causes uplifting and fracturing, which can create tilted or protruding rock surfaces.

-

Water Flow – Rivers and streams often cut into rock formations, leaving behind projecting cliffs and overhangs.

-

Glacial Activity – During ice ages, glaciers scraped and carved the land, leaving behind unique projecting formations.

Each projecting rock tells a story of the earth’s history, showing how natural forces have shaped the landscape over time.

Ecological Importance of Projecting Rocks

Beyond their geological significance, projecting rocks serve as habitats and ecosystems. Birds often nest on rocky ledges where predators cannot easily reach. Small mammals, reptiles, and insects also use cracks and crevices for shelter. In coastal environments, projecting rocks provide resting sites for seals, seabirds, and other marine life.

Vegetation also benefits from projecting rocks. Mosses, lichens, and hardy plants grow on their surfaces, while larger trees may establish roots in sheltered areas below them. These formations create microenvironments that support biodiversity.

Safety Concerns and Hazards

While projecting rocks are fascinating, they can also pose dangers in certain settings. Overhanging rocks along roadsides, hiking trails, or construction zones may loosen and fall due to erosion or seismic activity. Rockfalls are a significant hazard in mountainous regions, often leading to road closures, property damage, or injuries.

Engineers and geologists often assess projecting rocks near human settlements to determine their stability. Methods such as rock bolting, netting, and controlled blasting are sometimes used to prevent accidents. For hikers and climbers, understanding the risks associated with unstable projecting rocks is crucial for safety.

Cultural and Historical Significance

Throughout history, projecting rocks have captured human imagination and served as landmarks, shelters, and even sacred sites. Ancient people often used rock overhangs as natural shelters, leaving behind cave paintings and artifacts. Many cultures view dramatic rock projections as symbols of strength, endurance, or spirituality.

For example, in India and Africa, projecting rock formations are often tied to folklore and religious practices. In Western cultures, they have inspired artists, writers, and explorers. Tourists today are still drawn to famous projecting rocks, such as Norway’s Trolltunga or Australia’s Wave Rock, which showcase the awe-inspiring power of nature.

Projecting Rocks in Modern Use

Today, projecting rocks attract adventurers, climbers, and photographers. They are often focal points in natural parks and tourist destinations. Hikers enjoy the challenge of reaching these spots to take in breathtaking views, while geologists study them to understand the forces that shaped them.

In urban planning and engineering, projecting rocks are both an asset and a challenge. While they enhance natural beauty and attract visitors, they also require careful management to prevent hazards. Many cities and communities located in hilly regions invest in rock stabilization projects to protect infrastructure.

Preserving Projecting Rock Formations

Protecting projecting rocks is an important part of conservation. These formations are not just beautiful landscapes but also valuable geological and ecological resources. Conservation strategies include:

-

Establishing Protected Areas – National parks and reserves often include projecting rock formations within their boundaries.

-

Limiting Human Impact – Excessive climbing, vandalism, or tourism can damage delicate ecosystems around these rocks. Responsible tourism helps preserve them.

-

Scientific Research – Continuous study helps monitor erosion rates and predict future changes.

-

Community Awareness – Educating local communities about the importance of projecting rocks fosters respect and protection.

Conclusion

Projecting rocks are more than striking features in a landscape. They are products of millions of years of geological activity, vital ecosystems for wildlife, sources of cultural inspiration, and even modern challenges for safety and conservation. Whether seen on a coastal cliff, a mountain trail, or a desert plateau, these natural structures remind us of the power and artistry of nature. By understanding and protecting projecting rocks, we not only preserve geological history but also ensure that future generations can appreciate their beauty and significance.